Military & Veteran Affairs Reporting Guide

The Military & Veterans Affairs Reporting Guide helps reporters provide more accurate and more nuanced reporting on military and veteran issues.

See something you don’t think is right? Have a suggestion for how we could improve? Share it with us on our community feedback form located here!

Introduction to the style guide

Covering the military and veteran communities as a journalist isn’t an easy job. Service members and veterans are some of the harshest critics, and not all journalists covering the beat have served in the military. Even for those journalists who have served, it’s unlikely they know every detail about the branches of the military that they didn’t serve in.

This presents a problem.

There are too many dense and complex issues within the military and veteran communities for any one person to be an expert on. As a result, journalists are sometimes asked to produce stories on topics that they don’t have the time to fully learn about. The fallout from this ranges from salty veterans getting angry about the misuse of basic nomenclature, to military sexual assault victims being re-traumautized because of how a journalist tells their story.

Military Veterans in Journalism is setting out to change this. Thanks to a grant from News Corp Philanthropy, we’ve published this style guide and built an entire website dedicated to helping bridge the gap between the military and veteran communities and the media. We aim to accomplish this by offering context on complicated issues faced by our community, and by commissioning successful veterans in journalism to produce content that offers a deeper insight into military and veteran community issues.

We’ve solicited a range of journalists, media professionals and veterans throughout the production of this style guide, and we hope that this can effectively serve all journalists covering our community.

Thank you,

Zack Baddorf

Executive Director

Military Veterans in Journalism

1. Rank & Command Structure

A few of the pillars of life in the military are rank, command structure and terminology. A service member’s rank dictates a large part of their life in the military, and it’s important for journalists to understand how to properly address service members when covering them in news stories. It’s also important to understand how one rank fits in with another. Additionally, using the wrong terminology can instantly strip a journalist of their credibility.

For example, a sergeant would not be anyone’s “commanding officer,” as has been conflated in the past by some journalists.

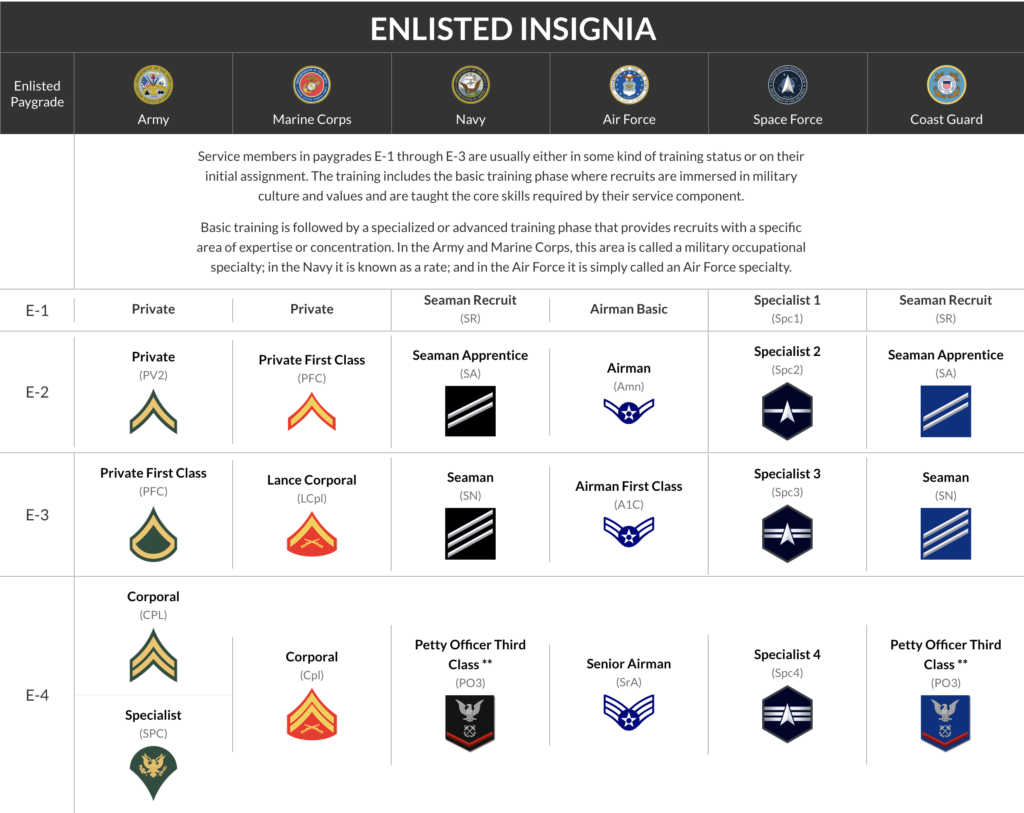

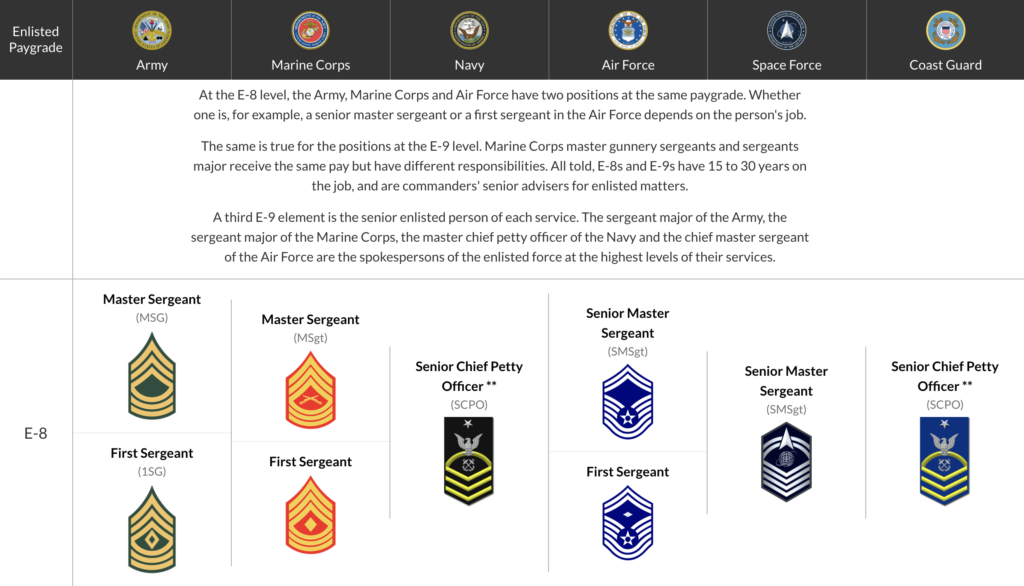

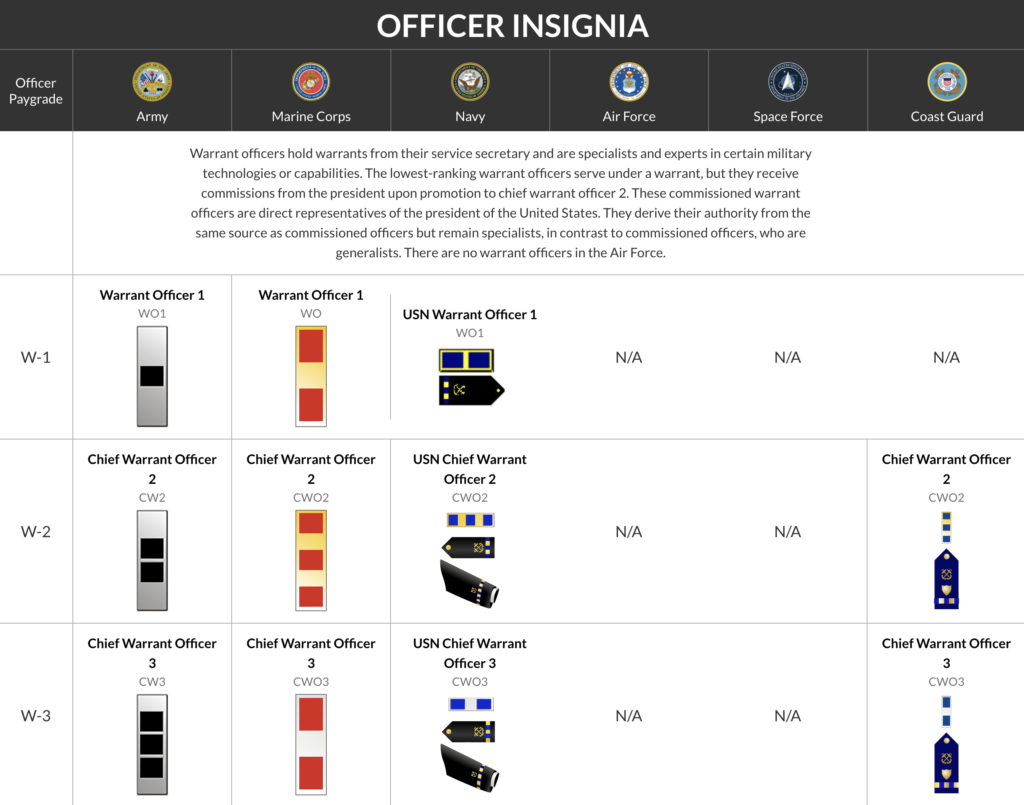

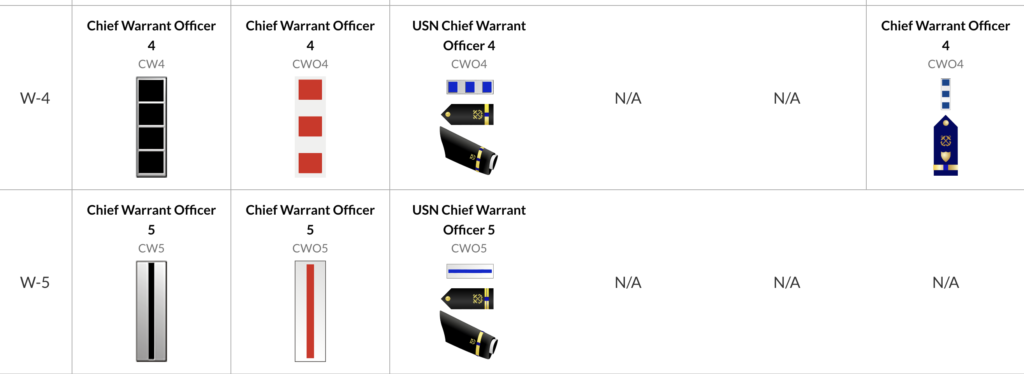

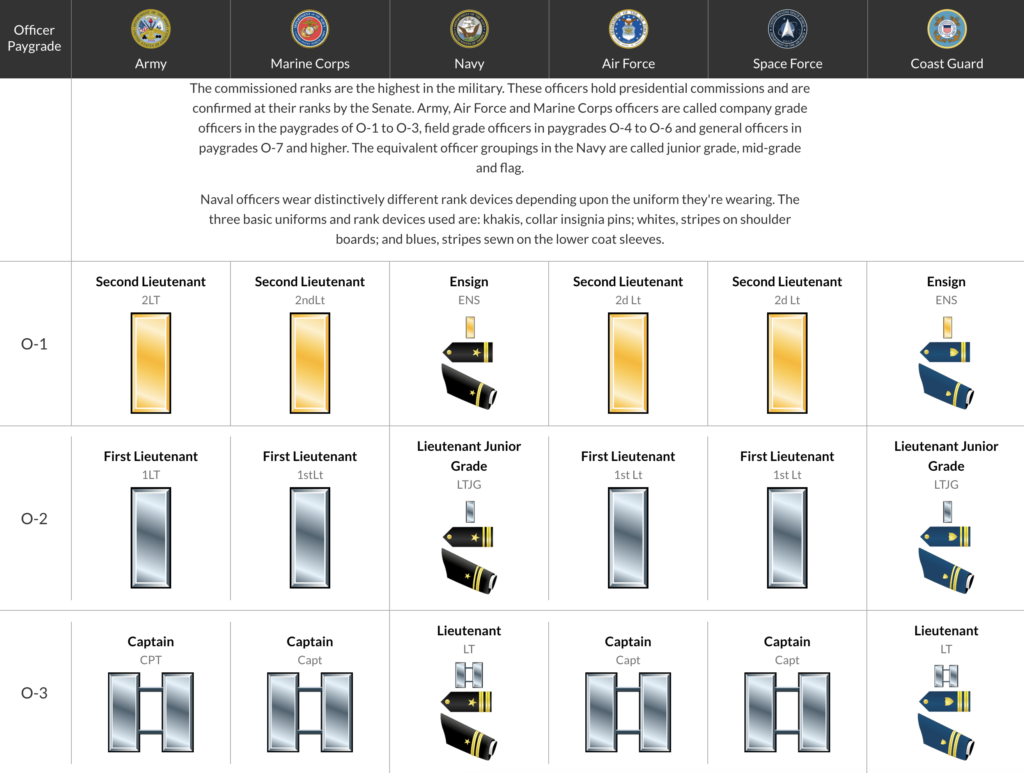

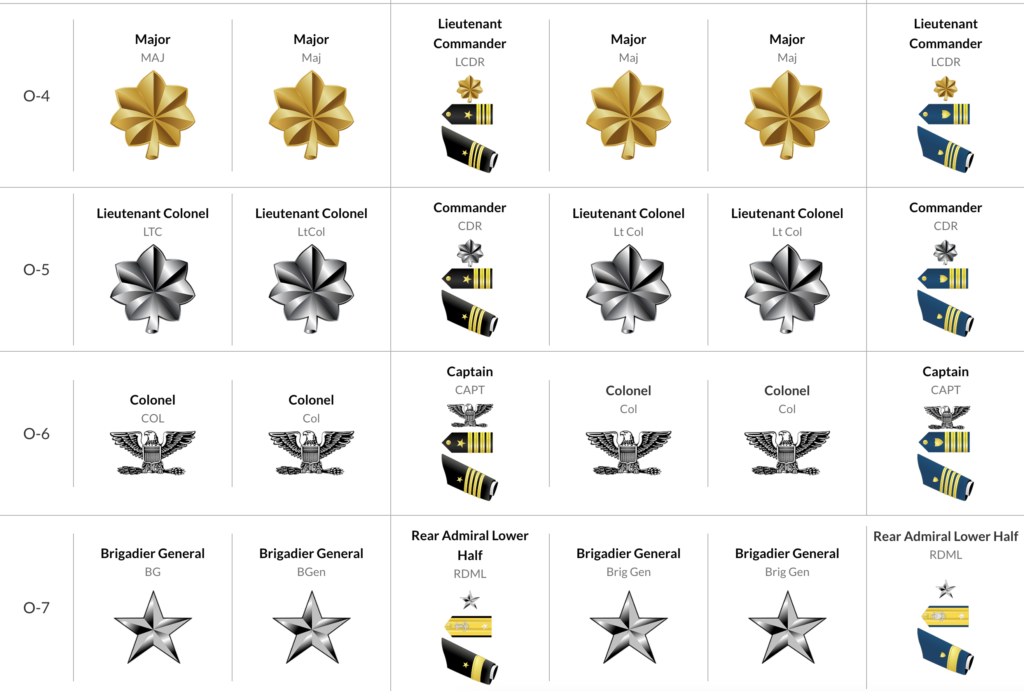

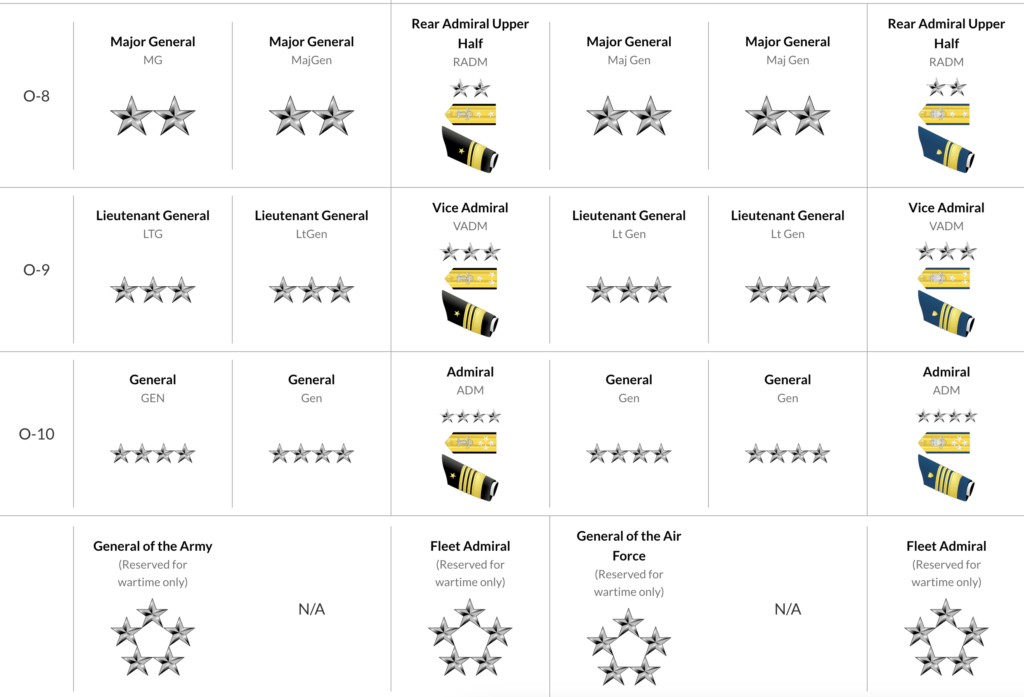

Each branch of service has its own rank structure, and command structures that fit within that framework. At the base level, every service has officer and enlisted ranks. Additionally, every branch except for the Air Force and Space Force also have warrant officer ranks.

Some important notes about differences between rank and pay grade must be noted. Each rank for officer and enlisted will have an “E,” “O,” or “W” before a number. The “E” signifies enlisted, the “O” signifies commissioned officer, and the “W” signifies warrant officer. The number after represents what pay grade they are in, but doesn’t always correlate with their rank. In the Army, for example, an E-4 can be a Specialist, or a Corporal. Corporal is a lateral promotion and is considered to be a noncommissioned officer (NCO) with leadership responsibilities that a Specialist may not have, but is still paid at the E-4 level.

Let’s take a look at each of the six service’s rank structures by way of charts.

Enlisted Ranks

Additional notes from DoD :

Army: * For rank and precedence within the Army, specialist ranks immediately below corporal. Among the services, however, rank and precedence are determined by paygrade.

Navy / Coast Guard: * A specialty mark in the center of a rating badge indicates the wearer’s particular rating. ** Gold stripes indicate 12 or more years of good conduct. *** 1. Master chief petty officer of the Navy and fleet and force master chief petty officers. 2. Command master chief petty officers wear silver stars. 3. Master chief petty officers wear silver stars and silver specialty rating marks.

Coast Guard: The Coast Guard is a part of the Department of Homeland Security in peacetime and the Navy in times of war. Coast Guard rank insignia are the same as the Navy except for color and the seaman recruit rank, which has one stripe.

Officer Ranks

Source: Department of Defense

Commander: A commander is a position that carries legal authority under the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ). Being a supervisor does not make you a commander. This is a revered position within the military, meaning commissioned officers compete for them and successful completion of command positions is required for promotion. Only an officer can be a commander.

Decorated: When referring to a service member or veteran who has earned numerous awards and medals, some journalists use this term as an adjective to emphasize a level of accomplishment. The term has no objective definition and should be avoided whenever possible.

Troops: Some use this term when referring to service members from various branches of the military. AP Stylebook 2022 (56th Edition) advises the use of “troops” in place of “soldiers”, etc. in updated guidance on writing about Marines.

Service member: Refers to any member of the U.S. military. If “troops” doesn’t fit your story, you can use this term instead. For example, “Service members use the commissary on military bases to buy groceries.” In this instance, service members may fit better than troops.

Noncommissioned Officer (NCO): A designation achieved at the E-5 rank which usually indicates a leadership position within the military, or if not directly in charge of others, a higher level of responsibility in their own job. NCOs and commissioned officers work hand-in-hand to accomplish the mission.

Commissioned officer: Someone who successfully completes one of the following commissioning programs:

1. Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC)

2. Officer Candidate School

3. Direct Commissioning programs (which is how lawyers and medical officers get their commissions)

4. One of the five U.S. service academies which are the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, U.S. Naval Academy, U.S. Air Force Academy, U.S. Coast Guard Academy and U.S. Merchant Marine Academy. Note: all of these academies offer commissioning programs into more than one branch of service after graduation.

5. The U.S. Army’s Green to Gold program. This program is administered by the ROTC program, but is specifically designed for enlisted soldiers to become officers and offers two, three and four-year programs.

These individuals can emerge from their commissioning source as an O-1 or O-3 officer depending on their skillset. Service academy, ROTC and OCS commissioned officers will always enter the service as an O-1, but a medical doctor pursuing a direct commission program may enter the military as an O-3 due to their MD qualification.

Note: When comparing officers and NCOs, you can think of the NCO as the hands-on manager and a commissioned officer as more of a director who oversees the bigger operation.

Soldier: refers to service members in the U.S. Army. Many journalists use this term to refer to service members in all branches of the military, but it is inappropriate and sometimes offensive to those serving in other branches. Refer to “troops” or “service members” above for more information.

Examples of bad reporting

LINK: National Guard officer retires with full benefits after ‘motorboating’ subordinate

WHY IT’S BAD: This is a perfect example of how a simple story that starts off good can quickly lose legitimacy among military and veteran readers. In the beginning of the article the victim (a U.S. Army sergeant) is referred to as a “subordinate soldier,” and then as a “junior solider.” Both references are somewhat acceptable, although if being picky the sergeant should be referred to as a “junior NCO.” Where this goes bad is the fourth graf — “In May while deployed to Jordan, the female officer declined to have a promotion ceremony.” This one line has the power to make people stop reading and shows a clear lack of understanding of the rank structure of the military.

Mistakes like these are easy to avoid and don’t require an in-depth knowledge of the military. It may seem like an inconsequential mistake, but it may come across as disingenuous and can cost newsrooms legitimacy in the eyes of the military and veteran community.

2. Military Awards

Service members work hard for their awards, and as journalists it’s important to get these award names and details correct when they show up in your story. For example, one of the biggest traps journalists fall into is writing that “the soldier won the Medal of Honor.” The Medal of Honor is not won, but rather is earned. This distinction can make the difference between a veteran reading what you wrote or simply ignoring it and holding it against you.

Below is an example of this practice reported on in the media:

Journalists finally advised to stop referring to all veterans as former snipers, Special Forces — Task & Purpose

Merit: Awards not earned as a result of battle but rather based on performance of one’s duties. Merit-based awards can still be awarded in combat zones.

Valor: Awards earned for valor indicate that they were earned in battle. The Department of Defense has an excellent chart on military awards for valor.

DoD Military Awards for Valor Chart

“V” Device: A “v” pin placed on a ribbon worn by a service member. Denotes personal valor (combat heroism) in combat with an enemy of the U.S.

Hero: This term should be used sparingly, as the term is so often used that many veterans see it as cheap clickbait in stories.

Read Scott Bourque’s piece Heroes, Victims, Messiahs to get a better idea of how using words like “hero” in your story can impact the veteran community.

Here is a (satirical) example of how not to write an article about military awards:

USMC soldier wins Congressional Medal of Honor — Duffel Blog

Combat Veteran: According to the VA and Title 38 of the United States Code, and for the purposes of VA healthcare, “a veteran who served on active duty in a theater of combat operations (as determined by the Secretary in consultation with the Secretary of Defense) during a period of war after the Persian Gulf War, or in combat against a hostile force during a period of hostilities (as defined in section 1712A(a)(2)(B) of this title) after November 11, 1998, is eligible for hospital care, medical services, and nursing home care under subsection (a)(2)(F) for any illness, notwithstanding that there is insufficient medical evidence to conclude that such condition is attributable to such service.” Essentially this means that the VA sees anyone who served in a combat zone or received hostile fire pay or imminent danger pay as a combat veteran.

Use of the term by the media is highly debated. To be safe, reporters should avoid using the term and instead be more specific when describing a veteran’s military service record. Consider consulting an expert from MVJ’s Expert Directory when putting together your piece.

Ranger: The U.S. Army cannot definitively say who is an “Army Ranger,” according to Task & Purpose. However, for our purposes we will define an Army Ranger as anyone who has served in the 75th Ranger Regiment. Those who have passed U.S. Army Ranger school and received their Ranger tab but only served in conventional units should not be referred to as Rangers, but instead as “Ranger qualified.”

Stolen Valor Act: A 2013 law making it unlawful to profit off fraudulent military service. People found simply wearing badges, rank or claiming service they did not earn are not subject to the law unless they profit in some way. The lowercase term stolen valor is sometimes used to describe a person’s lies about military service. Avoid unless in a direct quotation.

Military awards can be confusing to sort out and understand. When writing a story about a veteran or service member, getting their awards right is critical to how the story is received by the military and veteran population. Below are the official links to each branch’s awards, including explanations and criteria for earning each of them.

Note: At the time of publication, the Space Force does not have service-specific medals or ribbons. However, Space Force Guardians can wear awards from previous branches they served in.

Examples of bad reporting

WHY IT’S BAD: In an attempt to do something good, AP ended up getting it wrong when they referred to a Marine captain spending six years in Iraq. This may seem like a small mistake — and in a way it is — but the takeaway is that it costs the newsroom legitimacy in the eyes of service members and veterans.

Examples of good reporting

LINK: 50 Years Later, Four Vietnam Vets Awarded Medals of Honor in White House Ceremony

WHY IT’S GOOD: This story starts off right by beginning with the story of the veterans being awarded the Medal of Honor. Many newsrooms will just write a quick blurb explaining that the ceremony happened, share a quote from the president and maybe a quote from the citation. The reporter also exhibits attention to detail by using appropriate language throughout when describing the ceremony and awards given. Some newsrooms will use words like “won” when describing a service member or veteran receiving the Medal of Honor or other awards, which is incorrect.

3. Mental Health & Disability

Covering this topic as a journalist is a difficult undertaking. You must find a balance between acknowledging the sacrifices that service members and veterans have made, while not treating them like victims. Service members and veterans are, for the most part, quiet professionals who don’t want anyone to feel bad for them for the decision they made freely to serve.

Veteran Suicide and “22 a day:” an inflated number based on a 2012 VA Suicide Data Report. In this report, the VA gives the following disclaimer:

“It is important to note that estimates of the number of Veterans who died from suicide are based on information reported on state death certificates and may be subject to reporting error. It is recommended that the estimated number of Veterans be interpreted with caution due to the use of data from a sample of states and existing evidence of uncertainty in Veteran identifiers on U.S. death certificates.”

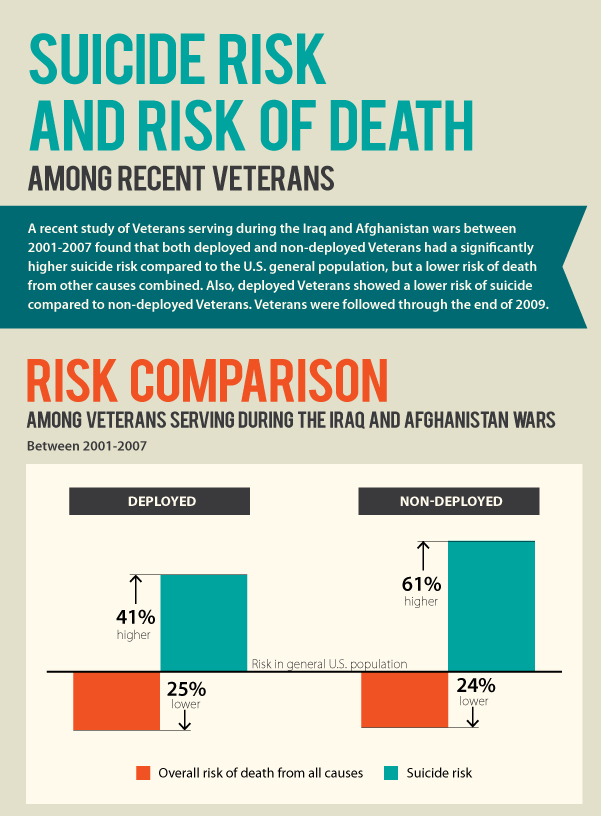

It’s also worth noting that when writing about suicide among service members or veterans it should not be assumed that combat trauma is what led to a service member or veteran commiting suicide. Though the VA data on this topic is aging, suicide rates have historically been found to be higher among those service members who never deployed to combat.

See the VA report here and a closer look at the 22 veteran suicides a day debate by Task & Purpose here.

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): a disorder not unique to the military in which someone has difficulty recovering after experiencing a traumatic event. Not every veteran who has deployed to combat has PTSD. It’s important to remember as journalists that PTSD can’t be attributed to every event in which a veteran commits a crime or act of violence. On the same note, veterans who do commit crimes as a result of their struggle with PTSD deserve a level of understanding and context with a deeper look at the “why” behind the story.

Examples of good reporting

LINK: The Fighter

WHY IT’S GOOD: C.J. Chivers provides an example of how a journalist can do deep reporting on a story that may have otherwise been written up quickly and published without affording readers a more in-depth understanding of how and why PTSD played such an important role in this story. Chivers spent a long time with the main character and truly got to know his story before publishing it. This type of reporting is what helps shed light on the complexities that many service members face when returning home from combat.

4. Military Sexual Trauma (MST)

According to the VA, one in three women and one in fifty men said that they experienced MST while serving in the military. MST, just like sexual trauma in civilian life, can be inflicted in many different ways. The stories from survivors are compelling and show the difficulties that MST victims endure before, during and after being assaulted.

The War Horse is a newsroom where journalists writing on this topic can go to seek more knowledge and read firsthand accounts. Here is their archive of stories on the topic.

Journalists should approach the MST topic with care. One of the most common issues in reporting on MST stories is re-traumatizing the victims by sharing their names or sharing unnecessary details that ultimately resurface trauma when victims come across the story.

Check out the VA’s fact sheet on MST to learn more and find additional resources that will help with your reporting. The Department of Defense Sexual Assault Prevention and Response (SAPR) also publishes reports on sexual assault in the military which can be found here.

Military Sexual Trauma (MST): MST is the term used by the VA to refer to experiences of sexual assault or sexual harassment experienced during military service.

Examples of good reporting

LINK: Trauma Reporting

WHY IT’S GOOD: Kelly Kennedy has years of experience reporting on trauma and the military. In this article she shares her experiences reporting on trauma and best practices for journalists reporting on the topic.

5. Public Affairs

Public affairs in the military can be thought of as the public relations department in any other corporation. Public affairs across all military branches generally consists of Public Affairs Officers (PAO) and Mass Communications Specialists.

PAOs are officers and their job is to make sure that their branch of the military or their specific unit is portrayed in the media in the most accurate and positive light possible. PAOs also advise military commanders on how to approach public relations issues and some even interface with Hollywood. They are most often the equivalent of a civilian PR representative.

Mass Communications Specialists are enlisted personnel who fill roles ranging from photojournalism to broadcast journalism and everything in between. Each branch refers to their enlisted public affairs with different titles, but they perform many of the same tasks as newsroom journalists in the civilian world. The public affairs army of each military branch produces print, broadcast and digital media, recruiting commercials and a host of other products.

PAOs are great for journalists looking to find sources for stories. If you’re writing about a certain branch, or a specific unit, search for a PAO associated with that unit and make the request. Sometimes you’ll have to send an email to a generic inbox to make the request such as a combatant command. Regardless, someone will eventually get back to you since PAOs depend on you just as much as you depend on them.

In 2019, the U.S. Army War College published a series of short pieces by War College graduates on the relationship between the military and media which provides a service member’s perspective on the history and current state of military/media relations.

Lastly, military public affairs publishes a plethora of content on DVIDs which is all free to use. You can also use DVIDs to create a media request.

Note: Please make sure to give credit to the service member who created the content; many journalists miss this.

Defense Visual Information Distribution Service (DVIDS): Provides an accurate, reliable source for media organizations to access U.S. service members and commanders deployed in support of military operations worldwide. (DVIDS mission statement)

Public Affairs Officer (PAO): Advises senior leaders in the military on public affairs strategies and decisions, and supervises communications personnel to ensure clear and effective communication about their branch of service with the public and civilian newsrooms.

Examples of good reporting

LINK: A Reporter’s Guide to Embedding With Military Forces

WHY IT’S GOOD: In addition to being a veteran, Ben Brody has embedded with the military as a reporter on numerous occasions. In this article he shares best practices and tips for how to succeed when dealing with PAOs and embedding with the military on reporting assignments.

6. The VA and Veteran Service Organizations (VSO)

There are thousands of VSOs in the U.S. Currently, over 100 are recognized by the VA, and many others exist who don’t work directly with the VA. At its core, a VSO is an organization that helps veterans with needs ranging from finding a home to getting a job. Some VSOs exist for one purpose and for certain veteran groups, while others exist for every veteran and provide many services.

Traditional VSO: longstanding VSOs such as the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars fall into this category. These well-established organizations are often found in physical locations throughout communities in the U.S. and help veterans with everything from VA disability claims to general companionship.

This is a list of the traditional VSOs that the VA works with most often: VA List of Traditional VSOs. This is a Frequently Asked Questions list published by the Congressional Research Service which helps answer some basic questions about VSOs.

7. Embedded Reporting

Military media embed programs became modernized during Operation Desert Storm, when accredited reporters would be granted access to military units during the first invasion of Iraq in 1990. The program was a public affairs coup, as reporters sharing risk, deprivation, and proximity with troops created bonds of affection which likely resulted in positive or at least uncritical reporting on these operations.

The media embed program was also the primary means for reporters to gain access to troops during the 2001-2021 Global War on Terror. As the program’s effectiveness in generating positive media coverage waned, the embed program in Afghanistan ended in 2014, leaving reporters few options when wishing to cover US military operations.

If you are able to apply for an embed, be aware that military public affairs officers (PAOs) will scrutinize your past articles and possibly your social media posts to assess the likelihood your visit will result in positive coverage for the unit. Freelancers will generally have to provide a letter from a media outlet stating their intent to publish your work resulting from the embed. In some cases, specific liability insurance will be required as well.

If you are granted a military embed, you will receive a packing list, which you should follow carefully – the military is not likely to loan body armor, sleeping bags, boots, etc. to reporters. Pack only what you can carry unassisted for a mile. Big roller cases are not advisable unless you have already made arrangements for your equipment. Traveling light will always get you deeper access on the battlefield. Military units will have very little patience for a reporter who can’t endure the same conditions that they do.

Carefully review the military embed ground rules and ask the PAO if you have any questions. The PAO is always your first point of contact during an embed – don’t try and get permission from a squad leader for something the PAO told you that you couldn’t do (all you’ll do is get the squad leader in trouble). PAOs also know a tremendous amount about the units they serve in, and the more you can tell them about your needs, the better they can place you within the unit.

Also, if your outlet allows it, it is not a bad idea to share your pictures with the soldiers you’re covering. They always appreciate it, and can often develop into good sources for you later on down the line.

A good PAO won’t sugarcoat failures within their command. They’ll have messaging that they want to get out to explain what happened and what they will do to correct any deficiencies; nonetheless, they are obliged to provide basic facts, barring legitimate security and privacy concerns and will want to provide accurate information. Your challenge while embedded will be to get beyond the talking points and to find more ground truth details. This can create an adversarial relationship – the PAO’s desire to keep on message vs. your desire for a more robust story – but it’s in your best interest to be professional and courteous with PAOs, who can be your best advocate or who alternately could be advising that their commander deny your request for information or access.

Examples of bad reporting

LINK: Military kicks Geraldo Rivera out of Iraq

WHY IT’S BAD: This is an older example, but the takeaway is still applicable. When embedding with a military unit, take special care to observe operational security and not share any specific information that could put U.S. service members at risk.

LINK: Navy Commander Accuses Miami Herald Reporter of Sexual Harassment

WHY IT’S BAD: According to the above article, former Miami Herald reporter Carol Rosenberg is accused of abusing military personnel while reporting on Guantanamo Bay. According to the article “While watching Sept. 11, 2001, co-defendant Mustafa al-Hawsawi seated on a pillow in court last year, Rosenberg told Gordon: “Have you ever had a red hot poker shoved up your [butt]? Have you ever had a broomstick shoved up your [butt]? . . . How would you know how it feels if it never happened to you? Admit it, you liked it.””

Examples of good reporting

LINK: Embedded with Special Forces in Afghanistan Part 1 & Part 2

WHY IT’S GOOD: In this two-part story by Marty Skovlund Jr., we get a rare glimpse into the later part of the war in Afghanistan. Throughout the video pieces, Marty pays mind to his diverse audience by taking the time to explain military terminology that not everyone understands. He also takes special care not to reveal any names, dates or locations that would be harmful if seen by any enemy forces. Finally, Marty made sure that he worked well with his military public affairs liaisons and unit commanders. He also made it clear what his role was and was not, and that even though he was a former special operations soldier, he was now in Afghanistan as a journalist.

8. Military Slang & Other Terms

POG: Personnel other than Grunt. This is a term used to describe non-infantry service members by salty infantrymen. It is often used and perceived as a derogatory term.

Pogie bait: Also known as “lickies and chewies,” this refers to snacks that one brings to the field when conducting training exercises. However, it often gets used in many other daily situations.

Fobbit: Derogatory term used to describe a person that doesn’t leave the Forward Operating Base (FOB). Those who leave “the wire,” or work outside of the confines of relative safety in the FOB, will often refer to those who don’t have jobs requiring them to leave the FOB as Fobbits.

Crunchies: A term used by tankers to describe infantrymen.

Field problem: This is a training exercise that requires service members to go to the field (the woods) for days or weeks at a time and conduct evolutionary training programs. From live fire exercises to complex raids and everything in between, almost all pre-deployment and pre-certification tasks take place in the field.

OPFOR: Opposing Forces. This is anyone in a field problem who is the “enemy” for the particular exercise. This is a spot filled by other U.S. service members and is a training term not used for actual enemy combatants in real-life situations.

Ranger Grave: A shallow hole dug to reduce the profile of service members occupying positions in the field who may be at risk of being spotted by opposing forces.

Slit Trench: A hole where a service member living in the field will utilize the bathroom.

Piss Tube: A tube (typically a PVC pipe) hammered into the ground where service members will urinate. The purpose is both hygiene and combat related. When living where you use the bathroom, avoiding contamination with human waste is important. Additionally, adversaries can smell human waste and it can indicate position and other information that shouldn’t be advertised when in combat.

Top: A term used to replace First Sergeant (E-8) by some. Different units and MOSs will either embrace this or forbid it, and each First Sergeant may have their own preference for this interchangeable term.

Gunny: Short for Gunnery Sergeant (E-7).

Slick Sleeve: Primarily an Army term, this is used to refer to those who haven’t deployed to a combat zone and therefore don’t have a patch on the right sleeve of their camouflage uniform.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV): UAV is a designation that has a specific meaning to an unmanned aircraft system. To avoid confusion, it is important to call this equipment by its intended name. Another example of this is the difference between a rocket and missile — a misperception that is often used in legacy media to describe a bomb, but in reality, the two are very different and imply different capabilities by the user. We should strive for that accuracy and acknowledge that many shorthands for these pieces of equipment may not only be harmful to communities, but inaccurate.

Kamikaze: “Kamikaze” is a Japanese word that refers to the Empire of Japan’s military pilots who were ordered to go on suicide missions during World War II, purposely crashing aircraft loaded with explosives onto targets, such as U.S. Navy ships. Lately, this term has been used to describe Russian attacks in Ukraine. But the term is not accurate (as most of the drones are unmanned and there is no suicide mission) and can be harmful to the Asian community.